The chill evening air of late September 1915 seeped through the greatcoats of the remaining men of A Company, 6th Battalion Somerset Light Infantry. They had seen a day of terrible fighting that had killed five of their number and wounded many more. Not far from the front line trench of Cambridge Road, near to the place the trench maps called Gully Farm, the half darkness allowed an element of formality in the burial of their five fallen comrades. Nonetheless, the cold, exhaustion and fear of enemy pot shots made for a hurried burial service. Temporary markers were placed and the men shuffled off to warmer billets and let the memories of the day wash over them.

A few short hours later, Lieutenant Colonel Rawling, commander of the battalion, was stuttering through the unenviable task of writing to the families of those buried in haste at Gully Farm. One such letter was to the relatively newly-wed wife of one of the battalion’s Company Commanders, Captain Henry Skrine. Of all the letters this may well have been the hardest of all for Rawling to compose.

Every officer in the battalion loved your husband, and showed most evident signs of sorrow when they heard of his death, a thing rarely done when they are surrounded, as at present, by terrible fighting.

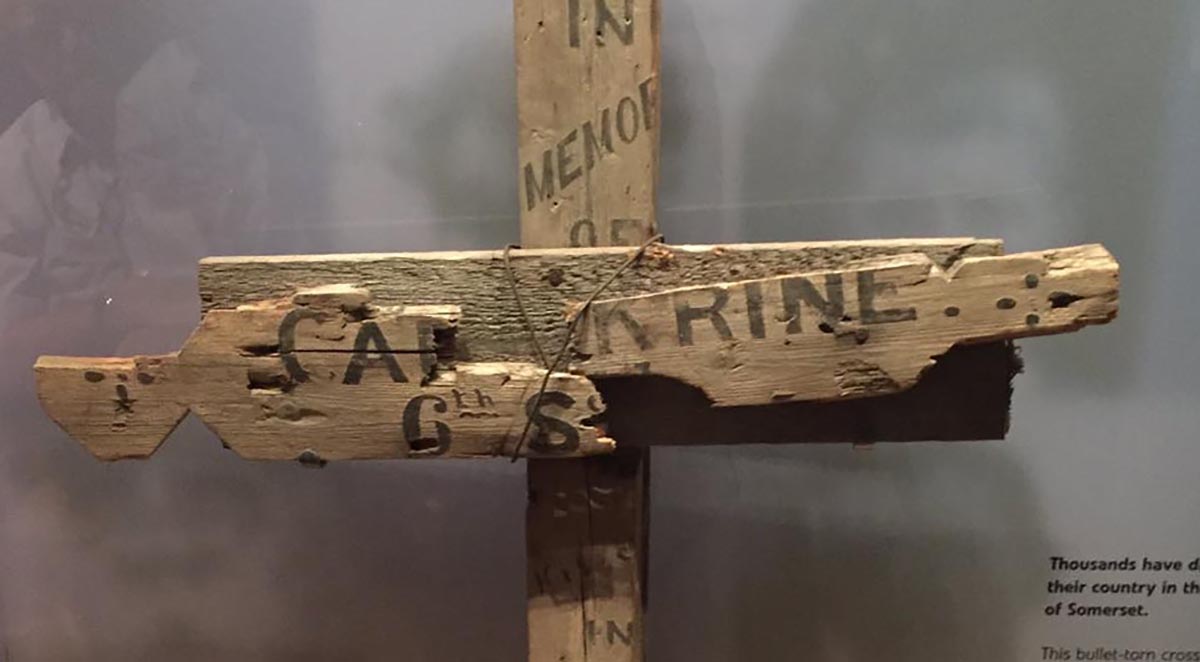

The words dripping off his pen were, no doubt, a marker of his own feelings to the loss of another officer. As a friend and fellow officer it was a stark blow, as a battalion commander it was no less impacting to lose a man of such ability. To compound things, Captain Skrine’s subaltern, Lt. Hawker, was also wounded in the fighting and the company was, in the words of Rawling, ‘desolate’. It was not just Rawling and his fellow officers who felt Skrine’s loss, ‘his company are deeply grieved, for he was not only a good leader, but a generous, sympathetic friend’. Amidst the platitudes of noble death, the emotion of Henry’s loss resonated through the words of his commanding officer. Whilst the battalion was still in the area, the graves were tidied and the markers made a little more permanent. Still wooden, still susceptible to the intervention of man and nature, but neatly and lovingly hand painted to mark the memory of a man dearly missed.

News of Henry’s death struck the family and the community hard. Just 10 days after his death, the local newspaper captured an extraordinary outpouring of grief, chalked onto the road near his family home at Warleigh Manor, ‘He did his duty do yours’. But, whilst the family grieved and the community grieved for more lost sons, the war raged on. The shellfire rolled across the same strips of land, devastating all before it. Even the damaged, shell hole-pitted Ypres Salient of late 1915 had been further reduced to a muddy moonscape. Just as the shell did not distinguish between the living, it did not distinguish between the dead. Somewhere in the years between that hasty evening burial and the end of the fighting, Henry’s grave, along with those of his men, were lost.

As 1919 dawned the great task of clearing the former battlefields of the dead and detritus of war began. One year later, in the ruins of that place on the trench map called Gully Farm, the battered and shattered ruins of a cross were found. The few distinguishable marks still legible on the splinters of wood marked it out as the cross placed over Henry’s grave. Alas, whilst the few fragments of the marker lovingly crafted and left in memory of Henry were all that remained, Henry was never found.

Another year on and the Bath Chronicle reported,

On the battlefield near Ypres, by the wayside where the ‘Cambridge Road’ touches Gully Farm, and which was part of the front line of the British Army in September, 1915, a rough hewn granite cross has recently been erected by the family at Warleigh Manor, to mark the place where Captain Henry Langton Skrine, and many gallant men of the 6th Somerset Light Infantry, gave their lives for King and Country in the Great War…The cross as it now stands, on a small piece of land purchased by the family at Warleigh.

The placing of this memorial may have been prompted by the discovery of this cross, it may have been a desire held by the family since the day Lieutenant Colonel Rawling’s letter had first arrived, the exact details will never be known. Alongside their own personal tribute to Henry, his family, sensitive to the fellowship of the battalion and communal loss, had inscribed on the memorial,

The placing of this memorial may have been prompted by the discovery of this cross, it may have been a desire held by the family since the day Lieutenant Colonel Rawling’s letter had first arrived, the exact details will never be known. Alongside their own personal tribute to Henry, his family, sensitive to the fellowship of the battalion and communal loss, had inscribed on the memorial,

In memory of the men of his Company who lie here with him

Henry’s name still echoes through the Salient of Ypres, in the family memorial at Gully Farm, in the hall of memory at the Menin Gate and in the form of a chair donated by one of his sisters, Margaret Mowll, to the St. George’s Church. The remnants of Henry’s grave marker were returned home to England. Of all the memorials to Henry, in Belgium and England, it is perhaps those splinters of a cross, placed above his body, by his comrades, that forms the most lasting connection between the spot he breathed his last breath and the earth in which he is still buried; a piece of England that is forever Gully Farm.

Post: Tim Fox-Godden

Original piece on the wooden cross in The Museum of Somerset in Taunton is here.

Photograph of Skrines’s memorial in the 1980s before it was moved courtesy of Paul Reed. Photograph of the wooden cross by Dan Raymond. Feature image is an illustration for this piece by Tim Fox-Godden.

A beautiful and poignant piece well written only what I would expect from Tim fox-godden, love the illustration also.

Tim … thank you for this. Henry Duncan Skrine is my Great Great Grandfather … via his daughter Ethel who married Douglas Close Richmond. Their daughter Isabel being my Grandmother. I look forward to visiting the museum at Taunton. Do you know where the Cross has been moved to . Is it still thee in Ypres somewhere?

Thank you

The granite cross can be found adjacent Cambridge Road (Begijnenbosstraat), just north of where that road crosses the Zuiderring (N37) a few miles east of Ieper. I visited it at the end of April this year. As you probably already know, there are also memorials at Claverton (a plaque) and Bathford (a stained-glass window).

Dear Dr Bell,

Could I ask if you are also connected to Lt Col Philip Roger Huntley Skrine, killed in WW2 in June 1941? I teach at Fettes College and he was one of our former pupils. It is always nice to hear about surviving relatives.

Best wishes

David McDowell